Arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance in Syria

Syrians deserve a future in which their basic human rights are respected. Without answers for the families of the missing, and without a dignified release for those still unaccounted for, Syrians will never be able to overcome the terrible wounds inflicted on them by war, dictatorship and radicalism.

Nine years on from the start of Syria’s uprising, arbitrary detention, forced disappearance and torture with impunity remain the weapons of choice in the regime and its rivals’ bids to subdue the people into silence. Even as it engages in internationally-backed peace talks, the regime continues to operate a widely documented system of detention where torture is near-inescapable and summary executions are endemic. Those who survive detention carry the emotional and physical scars forever. Over the years, other armed groups including ISIS also set up their own, parallel systems of detention, at a smaller yet no less brutal scale.

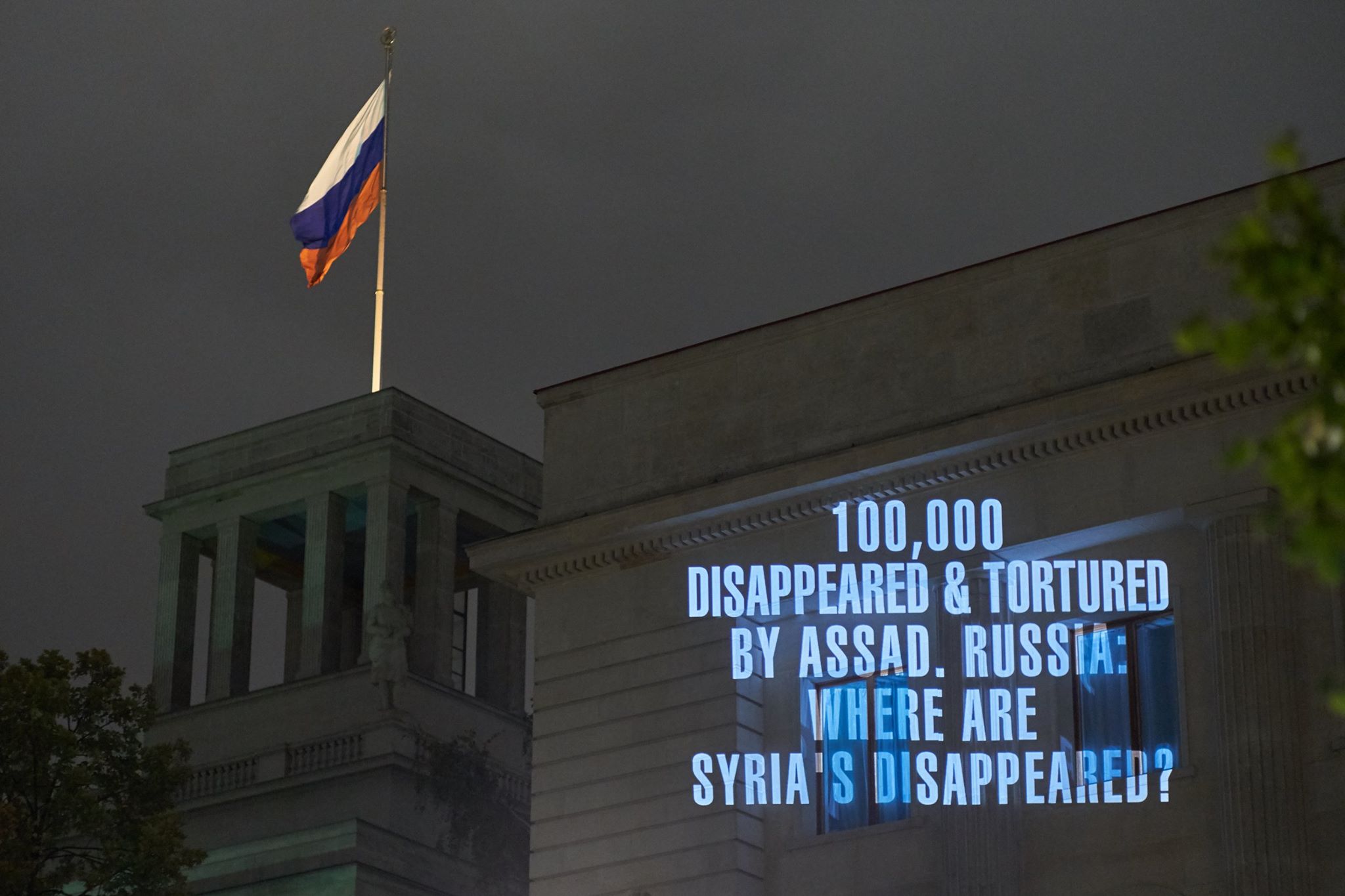

On the frontlines, the Russian-backed army uses its far superior firepower to crush any resistance. Meanwhile, in areas that have come back under Damascus’s control, hundreds more people are being detained, mostly leaving no trace for loved ones to follow, according to human rights activists who are documenting the recent disappearances.

The scale of the use of enforced disappearance by the Syrian regime amounts to the level of a crime against humanity, as confirmed by the United Nations. Despite this, the issue of the disappeared has been systematically marginalized at Syrian peace talks. Until this issue is properly addressed, there is no possibility of sustainable peace in Syria.

As of 2019, the Syrian Network for Human Rights documents that the number of people disappeared in Syria as at least 95,056 individuals.

The enforced disappearance campaign carried out by the Syrian regime since 2011 have been perpetrated as part of an organized, systematic and widespread attack against the civilian population. Therefore, it amounts to a crime against humanity, as confirmed by the United Nations Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic, and other UN bodies. The Assad regime has been enacting a policy of issuing ‘death certificates’ for some of those in detention. This is an attempt to deny its responsibility for the crime and to stop the efforts of family members to find the truth of what has happened.

Throughout the conflict, several non-state armed groups have used enforced disappearance as a weapon of war to get rid of opponents in their area of control, such as Jaysh al-Islam in Eastern Ghouta, Hayat Tahrir al-Sham (formerly Jabhat al-Nusra, formerly Al Qaeda in Syria) in Idlib, and ISIS in its controlled areas in Raqqa and Deir Ezzor cities and countryside. The use of enforced disappearance has been considered a war crime when committed by anti-Assad armed opposition groups and as a crime against humanity when committed by ISIS.

The end of the territorial control of non-state armed groups responsible for enforced disappearance, such as ISIS in northeast Syria and Jaysh al-Islam in Eastern Ghouta, has left families of the victims without access to evidence and answers.

Those in arbitrary detention or forcibly disappeared have not just been deprived of their liberty.

The systematic abuse against detainees in Syria’s jails has been widely documented and condemned. Human Rights Watch and Amnesty International, among other groups, have published damning reports of torture, rape, sexual violence and extrajudicial executions in prisons and detention centres scattered across the country. Many thousands have been tortured to death.

Who is detaining and disappearing civilians in Syria?

Now that the regime has gained the upper hand militarily and politically, its practice of detention with impunity is in full swing. Continued detentions send a message to the Syrian people that the Assad regime is in control and that it is not going anywhere.

Many of those people in arbitrary detention or forcibly disappeared have been missing for years. However the tactic of disappearing political opponents remains in widespread use to this day.

Some of the latest detentions appear to be part of a revenge campaign targeting those who dared to dream of freedom. Other recent detainees never had anything to do with politics, let alone take to the streets in protest. Experts on human rights in Syria say the practice of detention does far more than silence its victims. Detentions and forced disappearance send an unequivocal message to society as a whole: the regime is back in control, and anyone who questions its power pays the highest price.

Among those detained in recent months are people who took part in the very first protests in Damascus in 2011, but who quickly decided that it was best for them to stay out of the revolution. Others shared a single political post on Facebook in the early days of the uprising. While they may have forgotten what they posted almost a decade ago, the regime has not.

Meanwhile in Daraa province in southern Syria, 1,229 people have been detained since a reconciliation agreement was reached by delegations representing the local opposition, the regime and its backer Russia in the summer of 2018. Among the recent detainees were 42 women and 16 children, according to the Daraa Martyrs Documentation Office (DMDO).

According to Mohammad al-Sharaa of the DMDO, 29 of those detained despite signing reconciliation agreements in Daraa either died under torture, or were summarily executed in detention.

“The regime commits abuses against detainees in a systematic way, including rape. Most of the time, it is difficult to document the cases of female detainees because their families choose to remain silent, hoping that this will help keep them safe and prevent them from facing problems in prison,” Sharaa said.

In a report published on September 11, 2019, the UN Independent International Commission of Inquiry on Syria said it had received accounts of enforced disappearances throughout Daraa after the province was recaptured by the regime, “with the majority of victims being humanitarian workers deemed to have ‘betrayed the country’ for documenting attacks by the Government”.

According to the Syrian Network for Human Rights, 982 men, 96 women and 78 children who were detained or forcibly disappeared in Eastern Ghouta near Damascus between April 2018 and February 2020 remain unaccounted for. Like in Daraa, they too went missing after the so-called reconciliation agreements.

Sema Nassar, co-founder of the Urnammu for Justice and Human Rights foundation and one of Syria’s leading advocates for detainees’ rights, says victims of recent detention also include people who returned from abroad, either for a visit or with a view to resettle in their homeland, believing it was safe enough for them to do so.

The Syrian Network for Human Rights confirms this. “During 2019, we documented the arrest of at least 381 refugees who returned from countries of asylum to their original areas of residence in Syria,” the group says, adding that of that number, 113 were released — though most were then forcibly conscripted into the army.

And despite persistent calls from human rights groups for the regime to reveal the fate of those who have been jailed for years, at least 83,971 people detained since 2011 remain missing in regime jails and security branches, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

“Unfortunately there is no pressure on the regime to free the detainees and this issue is still put on the back burner without any genuine concern [from the international community]. And the regime cannot survive a single moment if it stops detaining people.”

Michel Shammas is one of Syria’s top human rights lawyers. He was forced to seek refuge in Germany in 2015 after he was targeted for arrest.

With torture a systematic practice in detention, it is likely that the majority have suffered horrific physical and psychological abuses in the labyrinth of the prison system, unaccounted for, with no access to justice and not knowing whether they will ever make it out alive.

As a result, hundreds of thousands more Syrians live in a painful limbo, deprived of information on the fate of relatives and friends who were detained over the course of the conflict.

The regime’s tried and tested system of detention is designed to terrorise its victims and their families and, by extension, cement its control over society as a whole.

Of course, Bashar al-Assad’s regime is not alone in its exercise of arbitrary detention and use of torture. Many months on from the Islamic State’s defeat in Syria in 2019 at the hands of the US-led coalition and its Kurdish-led allies, the fate of most of those kidnapped by the jihadist group remains unknown.

With no real push from the international community for accountability in Syria, it appears that the practices of detention and forced disappearance have become the cornerstone of the culture of power. Other armed factions including Hayat Tahrir al-Sham, the Kurdish-led Syrian Democratic Forces and armed opposition groups have also kidnapped thousands of people, according to the Syrian Network for Human Rights.

“We were scared when the reconciliation agreement was reached that this would happen because he had been working in an administrative post for several relief organisations. But we hoped it would be alright because many people were signing agreements, among them rebel group leaders”

Speaking on condition of anonymity, a young man described how his father, a former schoolteacher in Daraa province in southern Syria was detained in November 2018, despite having signed a reconciliation agreement with the regime.

The widespread use of arbitrary detention and enforced disappearance in Syria has prompted the emergence of some remarkable activist groups. Most notable has been the founding of a number of associations, made up of former detainees or people whose loved ones have been detained or disappeared. Groups such as Families For Freedom, Association of Detainees & The Missing in Saydnaya Prison, Caesar Families Association and Taafi have been at the forefront of activism on this issue. They have marched in the streets, staged protests, secured evidence, provided support to survivors and to each other, and much more. Many of the groups are based in multiple countries, as survivors and families have been forced to flee Syria. It is a huge risk for any of the groups to operate publicly in regime held parts of Syria, though individual acts of protest still occur.

The family and survivor associations all have different focuses for their campaigns and different policy demands. Some focus primarily on pushing for the release of detainees; others prioritise getting more information out on what has happened to their loved ones; and some are working on bringing those responsible for these crimes to justice.

International awareness of the issue of detention in Syria was greatly increased by the actions of one man – a defector from Syrian military intelligence, code-named Caesar. His work for military intelligence gave him access to the voluminous records kept by the Syrian regime of their detention infrastructure. Caesar secretly stole and then smuggled out of Syria 53,275 photographs of detention in Syria. The Caesar photos showed the world the shocking reality of detention in Syria. According to Human Rights Watch, the photos show at least 6,786 victims killed in detention.

Even as Syrian state media claims that peace has returned, for the families of the missing, one thing is clear: there can be no real peace in Syria without an end to impunity for the crime of forced disappearance. “How can there be peace, with most of my family still detained?” says Fadwa Mahmoud, whose husband Abdel Aziz al-Khayyer and 39-year-old son Maher have been missing since 2012. “What kind of reconstruction will there be — on the bodies of our children?”

Mahmoud is among the founders of Families for Freedom, a female-led collective of families advocating for truth and justice for detainees and victims of kidnapping in Syria. A lifelong activist, she describes how her husband, a doctor, was organising a peace conference in September 2012. Born in 1951, he believed a negotiated solution to end the nascent war was possible, even though he had spent 14 years in jail under the regime of Bashar al-Assad’s father, Hafez, for having dared to dream of a country where human rights and freedom were possible.

When he returned to Damascus from a short trip abroad on September 9, 2012, Khayyer never made it back from the airport. “He phoned me and said, Fadwa, send someone to pick me up,” Mahmoud said. “And I sent my son, Maher.” They never came home. The authorities told her they had no information on them, though she heard from another source that they had been taken for interrogation to the feared air force intelligence branch in Mazzeh, Damascus.

“For me it’s no longer about just Abdel Aziz and Maher — it is about all the missing,” said Mahmoud, who had also been jailed from 1992 and 1994 for being politically active. She believes Assad’s father used detention as a way to try to silence his opponents. “And the current regime is exactly the same. When a person is detained, they are not the only victim. The whole family is destroyed. Many families can’t afford to visit their loved ones in jail. Their goal is to break the spirit of anyone who dares to rise up, to break anyone who dares to dissent.”

“My dear son Maher, good morning to you. It’s your birthday today, I wish you a very happy birthday. I’ve been dreaming for the past eight years of celebrating your birthday with you here. But I will remain hopeful that the day will come. Be well. Wishes of freedom for you and for all detainees.”

Message posted by Fadwa Mahmoud on Facebook on January 2, 2020. Her husband Abdel Aziz al-Khayyer and 39-year-old son have been missing since 2012.

Hardly a day goes by for Mohammad Mounir al-Fakir without a flashback to Saydnaya prison, one of Syria’s most notorious. Detained from March 2012 to January 2014, human rights activist Fakir was first interrogated in various security branches and then transferred to Saydnaya, which Amnesty International described in a landmark report published in 2017 as a “human slaughterhouse” where the regime’s violations amount to crimes against humanity.

Like many other survivors of detention in Saydnaya, Fakir was emaciated when he was released. He says it was “a miracle” that he was released alive.

“Everyone who comes out of Saydnaya looks like I did, or worse. Some people’s bodies rot, even though they are still breathing. They are, sorry to put it this way, walking corpses. I was one of the lucky ones,” he says. “Stories of death in Saydnaya are constant. It’s more common to watch someone die in Saydnaya than to have access to food.”

The Association of Detainees and the Missing in Saydnaya in September 2019 published a report based on the testimonies of 401 survivors, detailing some of the violations.

“We identified 20 different methods [of torture]. The most common is beating with sticks and batons, as all the respondent detainees were subjected to this method of torture (100%). It is followed by whipping (95.2%) and then the ‘tyre’ (where victims are forced to insert their head, neck and legs into a car wheel, and then beaten; about 80.8%). Most detainees were also subjected to food deprivation and the pouring of cold water, and more than half were trampled by foot. A large proportion (more than 40%) were subjected to electric shocks, body suspension, and hanging, and the ‘wind carpet,’ (the victim’s hands are bound onto a flat surface, making it impossible for them to defend themselves, then beaten) and a quarter of detainees were tortured with the ‘German Chair.’ (the victim is forced to bend backwards and is tied to a chair and then beaten). About 15% were subjected to the maiming of faces and visible parts of the body, the pouring of boiling water, scalding with hot metal tools, immersion in cold water, and/or flaying. Excessive force-feeding is another method to which about 10% of detainees were exposed, and about 6% were subjected to dragging, crushing, and/or nail removal with pliers,” according to the report.

Fakir is a member of the association of survivors that published the report. Saydnaya, he says, “is an exceptionally grim prison, even by Syrian standards. It is a place designed for the Assad regime to take revenge against anyone who dared to rise up against it. They torture prisoners there to punish them — not to extract information. There are daily summary executions. And there is the military court, which also sentences people to death. People die there like flies.”

Amnesty International’s report detailed a system of mass execution in Saydnaya, which has seen thousands of people hanged. Fakir says he believes there were some 6,000 people held in Saydnaya when he was held there. “Now we believe there are around 2,000. Many have been executed, died under torture or died from disease,” he says.

Fakir says that unless the system of detention is shut down and that there is justice for the victims, there can be no real peace or return to Syria.

The end of the bombing alone will not bring people back. The sound of bombing may be louder, but nothing is as hard on the Syrian people as detention

Sema Nassar of Urnammu

“The issue of detention is central to the Syrian solution. Even if the regime says it is safe to return, people need confidence-building measures — meaning the release of the detainees and for the truth of the fate of the missing to be revealed,” he says. “From childhood, Syrians are warned not to talk, or else ‘they will take you away’.

According to Sema Nassar of Urnammu, an end to the bombing alone would never be enough to lay the foundations for a free, just political system in Syria. As such, many of the 5.5 million Syrians who were forced to flee their country in order to seek refuge abroad would not necessarily feel safe enough to return.

“The end of the bombing alone will not bring people back. The sound of bombing may be louder, but nothing is as hard on the Syrian people as detention,” she said.

This is how the regime remains strong — people frighten each other into submission. This is why this is the last thing the regime will agree to in negotiations. There can be no return or solution until the detainees issue is solved.”

No justice for victims of ISIS

Even now that ISIS has been crushed militarily by the US-led Global Coalition to Defeat ISIS and its Kurdish-led allies on the ground, the families of thousands of Syrians forcibly disappeared by the jihadist group have found precious few answers on the fate of their loved ones.

Amer Matar is a Syrian filmmaker living in Berlin, where he fled after he was twice detained by the regime. On August 13, 2013, his younger brother Mohammad Nour was kidnapped by ISIS. For years the family has struggled to find out what happened to the media activist. When ISIS was still in control of Raqa, their main former Syrian bastion, Matar’s mother was among the women who would hold protests in front of their headquarters demanding answers.

Matar says that soon after ISIS’s defeat in 2019, the family heard a rumour that Mohammad Nour had been seen at a hospital, being treated for severe asthma. But the rumour was never confirmed. “The only confirmed reports we heard came in the very first weeks of his disappearance,” Matar says. “But after the first months the information stopped coming, we started hearing only lies.”

As with families of people detained by the regime, Matar and his parents were repeatedly offered information on Mohammad Nour in exchange for large sums of money.

For Matar, there is no comfort in knowing that thousands of former ISIS fighters and their families are now held in prisons in Syria and Iraq. “Why aren’t the ISIS fighters being tried? It is not our right as victims of ISIS to see them tried?” he says. “Either they aren’t being tried at all or they are being tried in secret… There is no justice in this, either for them or for us.”

More broadly, to victims of ISIS violations like Matar’s family, there is little hope that the current negotiations to end the Syrian conflict will bring peace or justice. “We are talking about tens of thousands of disappeared, kidnapped or detained. Plus hundreds of thousands of dead. And millions of displaced people. How can people think of peace with all the dead?” Matar asks, adding that it is “very difficult to imagine peace” while victory is with the regime. “Even if they are defeated militarily the other sides will wait for their opportunity to take revenge,” he said.

“My brother Mohammad Nour Matar was always the rebel of the family. He was fearless, deeply courageous, yet very sociable,” Syrian filmmaker Amer Matar said. “He was the naughtiest of the three siblings, yet he was also very sweet and loving, and he had a great relationship with our parents. Whenever he would go to the Euphrates River, he would call me to say: ‘I am here, and I am thinking of you.’”

Mohammad Nour was born on July 14, 1993. The family has had no confirmation since the group’s defeat of whether he is dead or alive. They live in hope they might one day find him.

Stories of detention

The number of victims of the crime of arbitrary detention and forced disappearance are so huge as to almost defy human comprehension. Through the stories of individuals, we can get a better sense of what this issue has been so devastating, and why it is vital that it is addressed.

“Ayham, the joy of our household”

“Ayham was the joy of our household and family. He was a quiet, handsome son and a devoted dentistry student. He had many hobbies – he loved going to the gym with his brothers, and he was very talented at origami.

As soon as the Syrian uprising began, Ayham participated at every opportunity. He felt so proud to be in the streets with the protesters, singing and calling for freedom. I used to worry so much about him and the other young people – I always asked God to protect them. I once helped him hide flyers he wanted to bring with him to the university by sewing a secret pouch into his bag so that no one could see them if the bag was searched. When he came back from a demonstration, his eyes would be shining bright and his face filled with happiness and joy.

At that time, Ayham joined the Syrian Center for Media and Freedom of Expression. He was arrested for the first time in February 2012, along with his colleagues. He was detained for 86 days. Despite suffering extensive torture, he came out of prison smiling, hopeful that the revolution would defeat the unjust, corrupt regime.

He continued to juggle his study for a Masters degree and his work at a dental clinic while working to document the violations of the Assad regime. He participated in several workshops in Beirut on transitional justice. He was arrested just one day after his return from his last workshop in Beirut, on November 5th 2012. That was exactly seven years ago. He was with colleagues and students at the Dentistry Department of the University of Damascus when he was arrested.

During his arrest in the administrative hall of the university, Ayham was brutally tortured. Other students watched from afar, refusing to leave, as his nails were pulled, his ears were punctured, and his head was beaten viciously with a stick, resulting in complete loss of consciousness.

Ayham was then taken to Military Intelligence Branch 215. The other detainees, seeing that Ayham was unconscious and needed urgent medical attention, begged the guards to take him to a hospital, but one of the guards simply responded: “When he dies, call me.”

Ayham never regained consciousness. One of his friends who was held with him would check on him every few hours to see that he was still breathing. But five days later, the friend woke up to find Ayham’s body completely blue and cold. That was the morning of 11 November 2012.”

By Mariam Alhallak, mother of Ayham.

Yousef al-Haj Ali

Mawadda Haj Ali is now 10 years old.

In this photo, she was an infant with her father, Yousef al-Haj Ali. He was arrested from his home, and his family learned of his death through death certificates that the Syrian regime began issuing last year.

They learnt that Yousef was killed under torture on the same date yesterday in 2014, exactly five years ago. Mawada lived half of her life in hopes of seeing her father. Mawada’s mother found a folded piece of paper hidden between Mawada’s notes. The note of Mawada is below

” I miss my father, I envy my friends because they have a father, and then I wish I had a father who will love me and protect me. Well, I will not be going to make it long on this because it is my destiny, my friends, but really no one knows how much I suffer since I lost my father who used to protects us and offers us tenderness and love.

I’m so sad, I don’t know what my girlfriends are feeling when they have a father, I really don’t know the feeling anymore.

I hope that my father has not died and I hope he will return to us safely. Well, I became strong after my many sufferings and I feel that if my father was watching me from heaven that he would be satisfied with me.

My family would look beloved and perfect together with my father in it.”

“My brother Hamza”

” On August 13, 2012, my brother Hamza was arrested on his way back home on the road between Hama and Aleppo by the Assad Forces. Hamza was coming back from the university that day, he was preparing himself to start a bright future ahead after his graduation from the faculty of economics, he didn’t get to do that as the Divisions of Military Intelligence took his life away. Hamza was gone since then and we still don’t know the place of his body or the real date of his death “

By Nivin Almoussa, Hamza’s sister.

Take Action

There is still a chance for the international community to use its power and influence to demand justice. This means the release of all those detained in Syria who are still alive, the location of the burial sites of those who have been executed or tortured to death, and for who killed them to be held to account.

Families For Freedom are pushing for a United Nations Security Council resolution on this issue. To add your voice to the thousands of Syrian families who are calling out for freedom and justice for their loved ones who have been detained and forcibly disappeared by the Syrian regime and armed groups, please visit the Families For Freedom website and sign their petition.

It is also important for the US-led coalition and its partners the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF) to meet their responsibility to find the people disappeared by ISIS.

Sign the petition to urge the US-led coalition and its allies to immediately take steps that can uncover the fate of the disappeared by ISIS and give answers to their loved ones.

There are many associations that represent survivors and family members of the detained and disappeared in Syria. On their webpages, you can read more about their work and how to support them. The groups include:

Further resources

Policy guides on enforced disappearance

- No Impunity for Enforced Disappearance: Checklist for effective implementation of the International Convention for the Protection of All Persons from Enforced Disappearance. Amnesty International.

- Enforced Disappearance and Extrajudicial Execution: The Rights of Family Members. A Practitioners’ Guide. International Commission of Jurists

- The Right to Remedy and to Reparation for Gross Human Rights Violations. A Practitioners’ Guide. International Commission of Jurists

- The Right to Truth in the Americas. Inter-American Commission of Human Rights

- The Management of Dead Bodies after Disasters: A Field Manual for First Responders. ICRC.

Reports and articles

Human Slaughterhouse: Mass Hangings and Extermination at Saydnaya Prison, Syria. Amnesty International

Syrians Arrested, Killed Under Reconciliation Agreements. Syrian Justice and Accountability Center

Without a Trace: Enforced Disappearances in Syria. UN Independent Commission of Inquiry for the Syrian Arab Republic.

Syria: Detention, Harassment in Retaken Areas. Human Rights Watch.

The Assad Files. Ben Taub, The New Yorker.

A Deadly Welcome Awaits Syria’s Returning Refugees. Anchal Vohra, Foreign Policy.

A Tunnel With No End. The Syrian Network for Human Rights.

Silence, paranoia in decimated East Ghouta suburbs one year after government recapture. Ammar Hamou, Madeline Edwards, Syria Direct.

Syria: Mass Graves in Former ISIS Areas, Local Group Struggling to Recover Bodies, Preserve Evidence. Human Rights Watch.

Unearthing Atrocities: Mass Graves in Territory Formerly Controlled by ISIL. ICRC.